I’m All Lost In, #111: A counterculture weekly becomes a defining American paper; a failed Thanksgiving recipe becomes a masterpiece; a prescient poem about A.I.

I’m All Lost In …

the 3 things I’m obsessing about THIS week.

#111

1) Tricia Romano’s Oral History of the Village Voice is an Invaluable Work of U.S. History

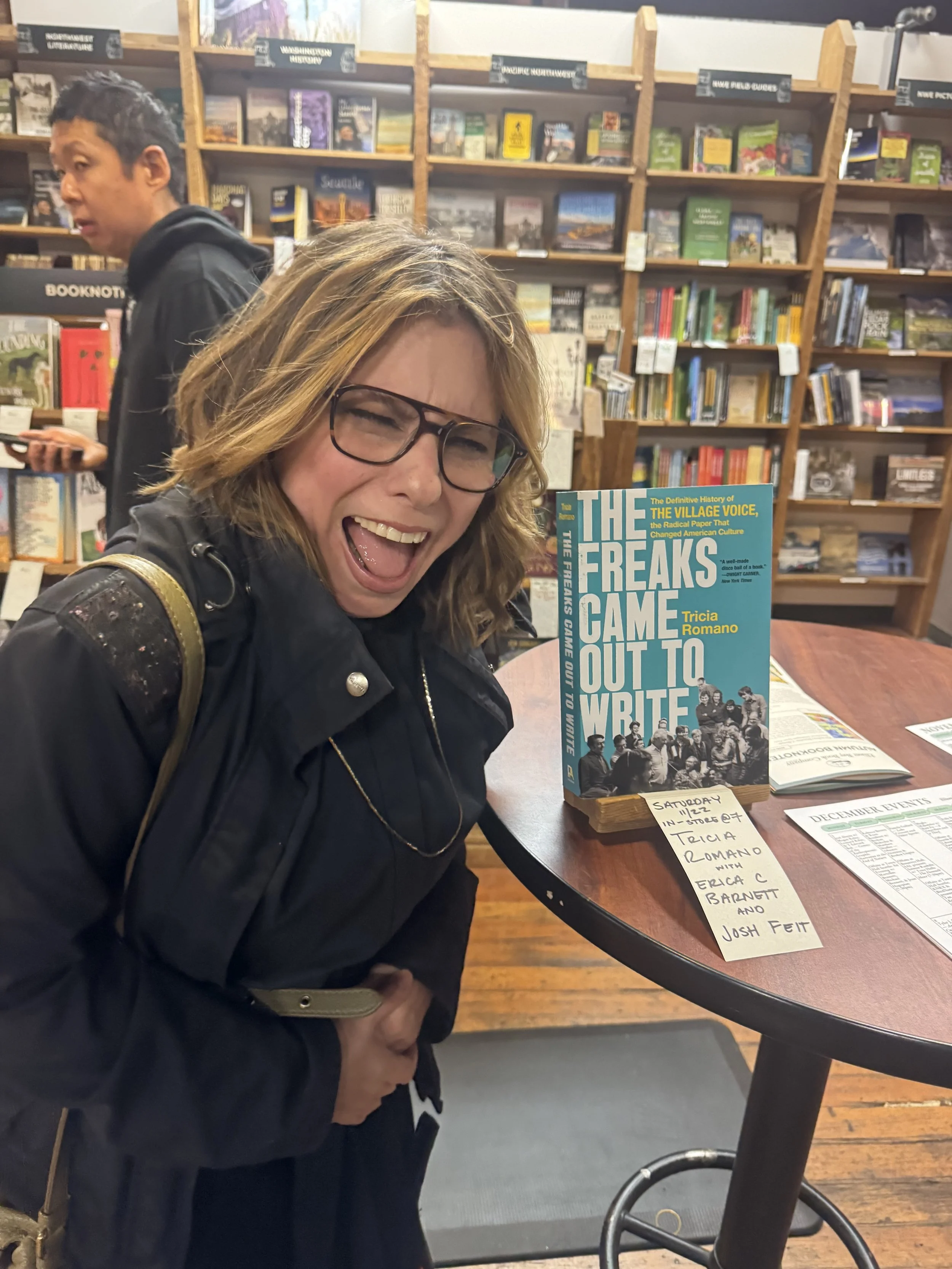

Tricia Romano, Elliott Bay Books, Saturday night, 11/22/25

L-R: Tricia Romano, ECB, and Me, Elliott Bay Books, 11/22/25.

On Saturday night, wearing our alt-weekly cred on our sleeves, ECB and I interviewed Seattle writer Tricia Romano at Elliott Bay Books. The occasion? The paperback release of her oral history about OG alt weekly the Village Voice. It was a finalist for the 2024 National Book Critics Circle Award.

Romano’s exhaustive roster of interviews, her well-informed outline, and her editing expertise translate into a must read for any student of American culture. She’s also done a heroic civic lift. The Freaks Came Out to Write: The Definitive History of the Village Voice, the Radical Paper That Changed American Culture is a national treasure; a default U.S. history seminar that appropriately captures the Village Voice in the many voices of its founders, writers, contributors, and editors as a mirror for the cultural throes of the mid and late-20th century.

The Hippies. The epic Women’s liberation movement (which apparently ruined the American workplace?). Transformative battles for free speech. Hip hop.

Over the course of Romano’s 530-page cornucopia of choice quotes, these seismic American currents happen in real time as the paper’s first-draft-of-history auteurs recount the wonderful tumult. The Voice’s tiny Sheridan Square offices at the time were just around the corner from the Stonewall Inn. The Voice had two reporters on the ground—one outside and one barricaded inside with the besieged police—as the lumpenproletariat wing of the LGBTQ community started pelting crooked cops with pennies and burning debris.

Howard Smith: At a certain point, it felt pretty dangerous to me, but I noticed that the cop that seemed in charge, he said, “You know what, we have to go inside for safety. Your choice, you can come in with us or you can stay out here with the crowd and report your stuff out here.” I said, “I can go in with you?” He said, “OK, let’s go.” He pulls his men inside. It’s the first time I’m… inside the Stonewall. It was getting worse and worse. People standing on cars, standing on garbage cans, screaming, yelling. The ones that came close, you could see their faces in rage.”

At a grander scale, Romano’s book highlights a subtle yet equally measurable ripple effect of the Village Voice: The paper’s elevation of pop culture criticism into a serious beat. The Voice was one of the first newspapers to champion the nascent weirdo punk scene at CBGB. (Credit where credit is due. the Voice’s counterculture cousin Rolling Stone also ran a 1975 article about CBGB. It focused on the Talking Heads. Patty Hearst was that month’s cover story.)

The Voice’s compatriot in the counterculture press, Rolling Stone, 10/23/75. Their famous Patty Hearst cover story. The issue also included a full-page, well ahead-of-the-curve dispatch from the burgeoning weirdo rock scene at CBGB.

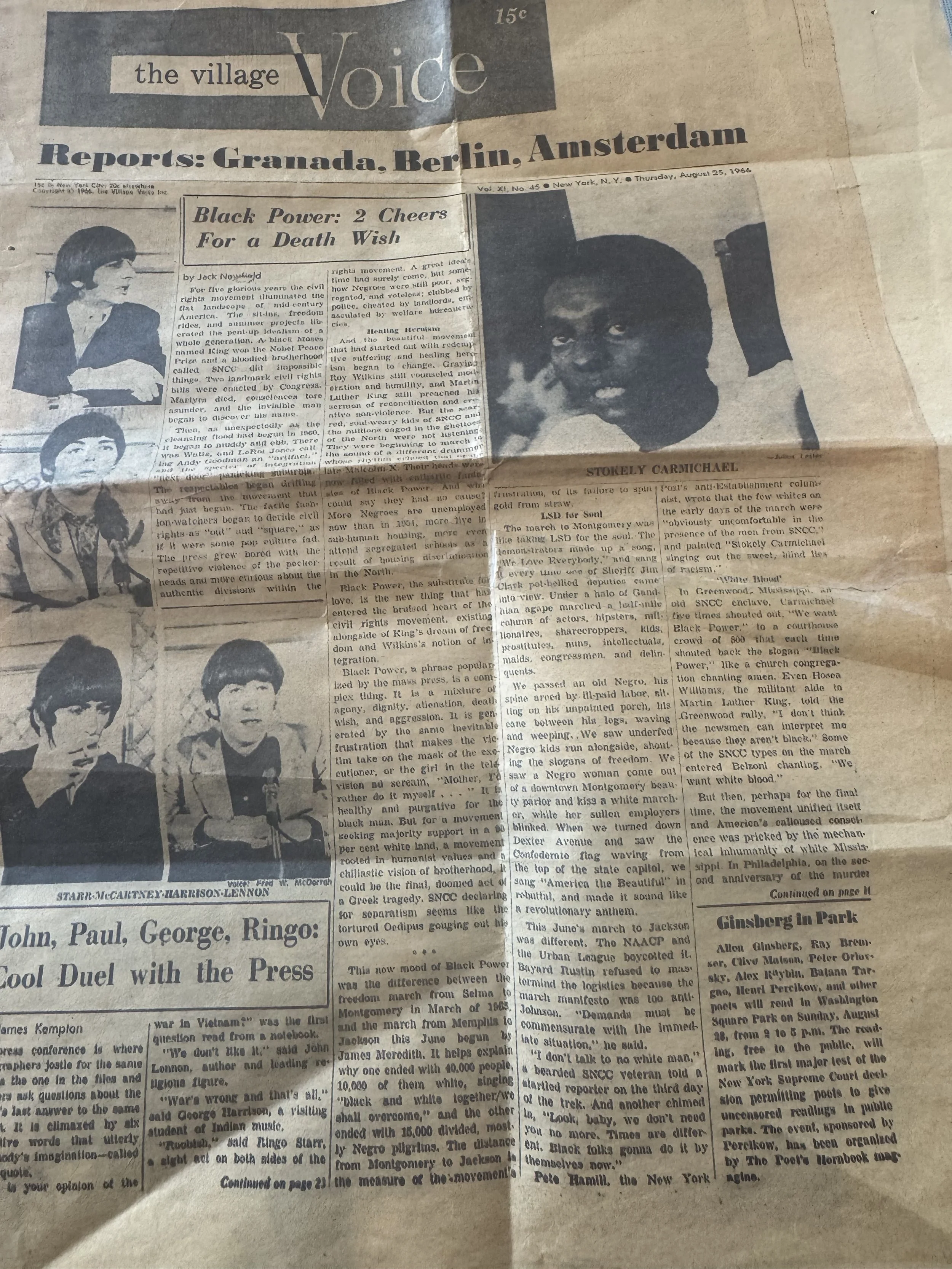

One of the questions I asked Romano during our Saturday evening interview: Why no direct discussion of the Civil Rights movement? Her book’s opening chapter, a 100-page whirlwind dedicated to the pivotal years 1955-1970 corresponds exactly with Rosa Parks’ civil disobedience on through H. Rap Brown’s militant resistance; RIP this week to Brown, aka Jamil Abdullah Amin. (I do know that the Voice covered the emergence of Black Power in 1966; many years ago I chased down the Voice from my birthday week. And there’s Stokely Carmichael on the cover.)

The Village Voice the week I was born.

Romano told me yes the Voice covered the civil rights movement. But the woman who covered it for them didn’t want to participate in Romano’s project.

Lots of women, Romano reports, had bad experiences at the male-dominated (Norman Mailer, Robert Christgau) Voice. And they had equally bad experiences trying to tell that story in other historical accounts.

Romano allowed that the Voice’s civil rights beat reporter was a woman named Marlene Nadle. I eagerly googled Nadle the next day. Turns out Nadle was a young white lady who was also an activist with the serious 1960s civil rights group, CORE. Her subjective role as a member of CORE fit the Voice’s “direct journalism” aesthetic: She had a front-row seat to the civil rights story. Literally. Nadle was on the chartered bus from Harlem to D.C. for 1963’s landmark March on Washington. Her embedded vantage informed her candid coverage and gave her an early peek at the story that would come to define the movement more publicly in the late 1960s: The intractable tension between Black activists and white liberals.

On my bus, there was a warning of the hostility between Blacks and whites in the movement that would intensify during the decade. In my dual role as reporter and white member of CORE, I heard a pale-faced liberal say, in patronizing tones, that he joined the Peace Corps and was going to Nigeria, “to help these people.” Wayne Kinsler, a piano-wire-tense Black member of my CORE chapter, shouted in response, “If this thing comes to violence, yours will be the first throat we cut.”

That anecdote is from Nadle’s own account of her work at the Voice.

My sub-obsession this week: Nadle. She had this to say about the fateful 1964 Democratic National Convention when LBJ abandoned Mississippi civil rights hero Fannie Lou Hamer.

My participation as an activist was important when I witnessed history at the 1964 Democratic Convention, in Atlantic City. It gave me access to some places closed to journalists. It also gave me a unique perspective on a turning point for the civil rights movement. The main issue at the convention was whether the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, organized by the civil rights movement, would be given credentials as the state’s official delegation and replace the current, all-white Mississippi delegation.

President Johnson failed the moral test and killed the Freedom Party challenge. The man who had passed the Civil Rights Act a month earlier had his supporters threaten members of the Credential Committee with a loss of judgeships, of loans, and of other local goodies, if they voted to give the Freedom Party the delegate credentials. The members of the Credential Committee offered the challengers only two non-voting delegate seats. When I slipped into a closed movement meeting, I saw muckety-muck liberals and some civil rights leaders pressure the Freedom Party to accept the worthless offer. The challengers refused. As the party’s co-founder Fannie Lou Hamer said, “We didn’t come all this way for no two seats when all of us is tired.”

My story stripped away the pretense that Johnson and the liberals had given the Freedom Party much of anything. It was permeated with the sense of betrayal felt by the delegates and the civil rights activists who came to the convention to fight for a Freedom Party win. Their naïve expectations and mine were buried in the sands of Atlantic City. Once, we believed all we had to do was reveal a wrong and the good people would fix it. The convention was so disillusioning that things were never the same. Bitterness replaced idealism, and trust in Johnson and the liberals died.

I’ve always hypothesized that the breakdown at the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City in 1964 foreshadowed the more infamous shattering that went down at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968.

2. Mushroom Ragu Meets Vegan Creamed Spinach

The Mushroom Ragu recipe called for “1 cup polenta (coarse cornmeal).”

I understood this to mean either (or). But after “one to two minutes of whisking,” the polenta wasn’t “starting to slightly thicken.” I suspected something had gone terribly wrong.

I didn’t have any cornmeal in my cupboard, but a cup of flaxseed meal thickened the veggie broth concoction right away. It also ruined the mushroom ragu recipe.

Fortuitously, I had decided to make three dishes for Thanksgiving this year. So, also in play in the kitchen during this disaster: 1) Best Vegan Mac & Cheese (cashews, nutritional yeast, garlic powder, salt, water and lemon juice) topped with panko bread crumbs, spray-on olive oil, and vegan butter; and 2) Creamy Vegan Greens.

The mac & cheese is a time-tested standby hit. And the creamy vegan greens (sautéed kale and spinach, thinly sliced sweet onions, chopped garlic, white miso paste, a cup of canned low-fat coconut milk, cayenne pepper, Kosher salt, black pepper, and nooch) was shaping up as a new favorite; I was taste testing as I went. It also seemed to me that this healthy hippie dish would become even tastier if I combined it with the discarded mushroom ragu from the flaxseed meal polenta fail.

An hour before I was due to annual 4:30 Thanksgiving at David Byrne’s (aka Dan’s) and Sara’s I improvised. I spooned the mushroom ragu (baby bella and T & T oyster mushrooms, crushed garlic, thyme, rosemary, red pepper, a cup of white wine, a can of diced tomatoes, vegetable broth, cornstarch, cracked black pepper, and salt to taste) into the kale and spinach dish.

I headed out the door at 4:25 with the cashew-heavy mac & cheese and the creamed-greens-plus-mushroom-ragu feeling like a kitchen genius.

3. A.I. was the Topic of Discussion at Thanksgiving 2025. A 1961 Poem by Adrienne Rich was 64 years Ahead of Its Time

20th century poet and feminist Adrienne Rich.

I’ve only read one of her books. Snapshots of a daughter-in-law: poems, 1954–1962.

I don’t know. An indie-rock Sylvia Plath? I loved it in 2020.

Happenstance: This week, I was looking for a poem I remembered reading in that collection about one of my favorite topics, airports. After reading that one—it’s called To the Airport, I came across a different Rich poem on the following page: 1961’s Artificial Intelligence (To G. P. S.)

First of all. “G.P.S.” Whoa, that certainly feels spooky. But it’s actually a topical 1961 reference to a 1957 computer program known as General Problem Solver.

Rich’s precursor machine-learning poem takes up the same issues that anxious and bewildered human beings are mulling today: Is A.I. sampling human thought as a means to render human thought irrelevant?

Rich’s rejoinder, just like ours 60+ years on, posits that A.I. is not threatening, nor as impressive as the human brain because it will eventually idle in dead-end loops, unable to come up with anything original. A.I. doesn’t dream.

Her last stanza:

Still, when/

they make you write your poems, later on,/

who’d envy you, force-fed/

on all those variorum/

editions of our primitive endeavors,/

those frozen pemmican language-rations/

they’ll cram you with? denied/

our luxury of nausea, you/

forget nothing, have no dreams.

Not only does Rich identify luscious existential nausea as a human tell, but earlier, in the first stanza of the poem, she rebelliously revels in another human joy: free association

Over the chessboard now,/

Your Artificiality concludes/

a final check; rests; broods—/

no—sorts and stacks a file of memories,/

while I/

concede the victory, bow,/

and slouch among my free associations./

My favorite moment though is her dramatic and macho pause in the fifth line. The all by itself: “while I.” Human pride, whatever it’s worth for the moment.

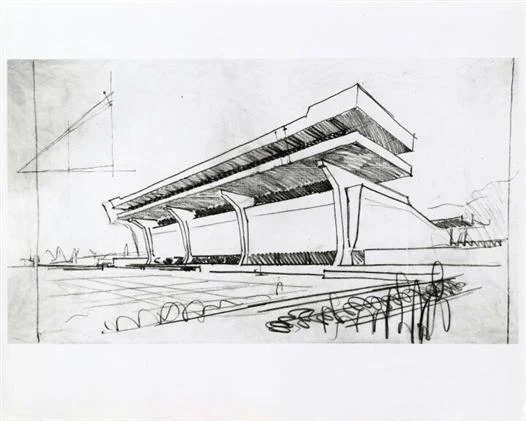

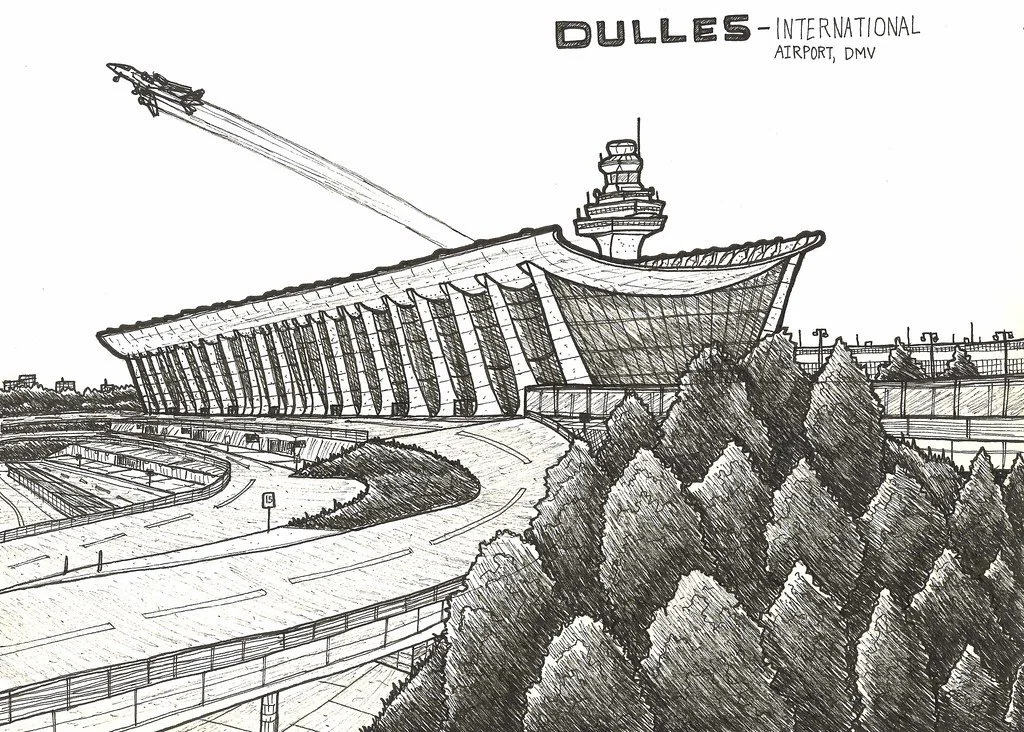

Speaking of my favorite thing—airports [I’m All Lost In, #93, 7/27/25]—here’s my pick for Drawings of the Week: Finnish architect Ero Saarinen’s late 1950s sketches for his tour de force project: Dulles International Airport:

And here’s Dulles airport fully realized when it opened shortly after Saarinen’s premature death at 51 in 1961:

Lastly: Gleaned this holiday week from cosying up with my Abstract R & B electronica, rave, and moody playlist, here are some Music Recommendations: Tristan Arp’s 2024 track Time Dilation; the Muslimgauze’s 2015 track Abyssinia Selasie; and two Dan Nicholl’s tracks, 2021’s Papa and Those Hills Hold You.

Electronic-remix-musician Nicholl’s track Those Hills Hold You was certainly (and lovingly) stolen from 1970s and ‘80s electronica pioneer Paul Lansky’s disorienting and lulling 1979 linear coding study Six Fantasies on a poem by Thomas Campion: Her Song.