Absolute Beginner Blues

“Well, I looked at my watch, it was ten o-five,

Man, I didn't know whether I was dead or alive!

But I was rollin', reelin' and a-rockin'...

Well, I looked at my watch, it was ten twenty-six,

But I'm a keep on dancin' till I got my kicks!

We were reelin', reelin' and a- rockin'...

Well, I looked at my watch, it was ten twenty-eight,

I gotta get my kicks before it gets too late!

We were reelin', reelin' and a- rockin' ...”

—Chuck Berry, Reelin’ and Rockin’ , B-Side to “Sweet Little Sixteen,” 1957

“Oh, well, I look at my watch, it says nine twenty-five

And I think ‘Oh God, I'm still alive’” —David Bowie, Time, from “Aladdin Sane,” 1973

Intro: Euphoria

I apologize in advance for this man-splainy atrocity. As my best friend Erica might derisively say: this is a “Boy Lecture.” It’s definitely a white guy lecture. Worse, it’s about 1950s Rock & Roll. And I’m not even a Baby Boomer. I’m a Gen-Xer.

But I love to play 1950s Rock & Roll on piano, and I can’t stop thinking about it.

Early 1950s Rock & Roll sparks euphoria in my brain. I don’t know why. I’m a 1980s teen—15 in 1982—who loved David Bowie and WHFS radio, Washington, D.C.’s underground station (“alternative” wasn’t a word yet).

Three and a half decades later, under the influence of my weekly Saturday afternoon routine (listening to Uncle Marv Goldberg’s “Yesterday’s Memories Rhythm & Blues Party” in the shower), I started taking piano lessons. I had a fantasy that in 10 years, I’d be able to walk into my future apartment, a gorgeous two-story condo with hard wood floors and high white walls, sit down at my expensive piano and smash out beautiful Stride-influenced jams when I got home from work.

With this Jerry Lee Lewis dream in mind, I stuck with formal lessons for about a year from a teacher who lived in my neighborhood. Unfortunately, she didn’t have a feel for Rock & Roll; one time, I brought in the sheet music to Ike Turner’s 1951 No. 1 R&B hit Rocket ’88, and she was flummoxed. During lessons, she mostly talked about the Feldenkrais method. And at best, Boogie Woogie Bear was my Twinkle Twinkle Little Star. I did learn to sight read a little, though, and she taught me some helpful hand positions.

A couple of years later, in December 2020, I made New Year’s resolution: By the end of 2021, I would be able to play a set of 1950s Rock & Roll songs on piano.

By early August, I had sort of learned 12 songs; I was still shaky on most of them because when I spent time learning one song, I’d forget an earlier one. Plus. I’m just not very good. Realizing I had five full months left in 2021, I decided I’d dedicate the rest of the year to working on these songs rather than adding any more.

As August comes to a close now (today is August 26th), my song-by-song review is going well. The songs I learned early in the year are further along than I thought they were. As opposed to re-learning them from scratch, I’m actually spending time discovering cool nuances that I didn’t have down earlier, or that I totally missed the first time, like moving the right hand (not just the left hand bass line) to the lovely IV chord—Eflat/A/C over the walking F bass line—on Big Joe Turner’s Shake Rattle and Roll.

I know songs with tricky beats like Calypso Blues will continue to bedevil me as I make my way through the set. And getting up to speed, literally, on bangers like At the Hop remains intimidating to an absolute beginner like me. But I’m feeling energized by this project. .

The euphoria I feel when I play these songs isn’t just about pressing my fingers into glorious chords such as the heavenly A sharp/G sharp/D/F sharp/A sharp arpeggio in Chuck Berry’s School Days. There’s also a sense that these 12 songs, which I chose iteratively over the first half of the year, have a collective narrative.

Here are the songs in my 2021 piano repertoire (in the order I learned them):

1. In the Still of the Night (The Five Satins, 1956)

2. Junco Partner Blues (Worthless Man) (James Wayne, 1951)

3. Heartbreak Hotel (Elvis Presley, 1956)

4. Earth Angel (The Penguins, 1954)

5. Shake Rattle and Roll (Big Joe Turner, 1954)

6. Rock Around the Clock (Bill Haley & His Comets, 1954)

7. School Days (Chuck Berry, 1957)

8. Calypso Blues (Nat King Cole, 1950)

9. At the Hop (Danny & the Juniors, 1957)

10. Rudy, a Message to You (Dandy Livingstone, 1967)

11. Get a Job (The Silhouettes, 1957)

12. Come On Eileen (Dexys Midnight Runners, 1982)

To explain the through line of this set, let’s start with the obvious outlier on the list, Come on Eileen.

Note: I am going to capitalize the names of musical styles. For example: Blues, Punk, Soul, Rock & Roll

1. Come on Eileen: 1980s Soul revival

As opposed to all the 1950s “Golden Oldies” that make up the supermajority of my set, Come on Eileen, a post-Punk, Gen-X Pop hit, is from 1982. Just like following a dropdown menu path, this early ‘80s British record establishes the first step in the sequence that guides my piano repertoire:

Soul music revivalism > original 1960s Soul > 1960s Ska > the Roots of Ska, 1950s Calypso > Calypso’s Diaspora twin, 1950’s U.S. Rhythm & Blues > 1950s Rock & Roll > 1950s Doo-wop.

Come on Eileen was written and recorded by a British Pop band called Dexys Midnight Runners starring ex-Killjoys Punk front-man, Irish songwriter Kevin Rowland. Dexys Midnight Runners were part of an early 1980s British crop of bands intent on reviving, or at least celebrating, London’s mid-1960s teen scene heyday with an ‘80s New Wave update. Dexys Midnight Runners—dexy is short for Dexedrine, an amphetamine popular with mid-60s Mod youth—used layered horn arrangements, swift bass lines, falsetto vocal figures, swirling keyboards, jukebox-friendly melodies, and SNCC overalls (plus bandanas and mascara), as they conjured Soul music, a primary artifact of the mid-‘60s scene.

With their 1980 debut LP, sentimentally titled “Searching for the Young Soul Rebels,” and featuring Geno, their hit single tribute to ‘60s African American ex-pat British Soul singer Geno Washington, Dexys became leading figures in England’s retro “Northern Soul” movement. Northern Soul worshiped deep 1960s dance cuts, predominantly from the African American Soul catalogue. Dexys claimed to eschew Motown in favor of channeling lesser known material, but their driving bass lines were pure Supremes; check out snappy Dexys’ tunes such as Seven Days Too Long, Let’s Make this Precious, and Keep It. Meanwhile, Rowland’s dramatic croon was a hybrid of Culture Club’s Boy George and Motown’s Levi Stubbs from the Four Tops.

In addition to mid-‘60s American Soul music, another signifier popular with the early ‘80’s bands was the mid-60s barre-chord garage Rock that pre-dated bombastic and psychedelic late-60s Album Rock. The Power Pop band the Jam defined this exuberant wing of the movement. The Jam were my favorite band from this early ‘80s era; I wasn’t a Dexys Midnight Runners fan, although the two bands occupied kindred factions in the revivalist movement. (And I did like Come On Eileen. How could you not?) While Dexys Midnight Runners, along with Blue Eyed Soul cohorts like Culture Club and Haircut 100, went for bass grooves, the Jam were guitar-driven, jacked up on precursor Punk Kinks riffs and Pete Townshend’s pre-“Tommy,” pop-art Who.

The Jam also had an affinity for 1950s and 1960s African American songwriters. They started out playing amphetamine-tempo versions of early African American Rock & Roll and Soul tunes, including Larry Williams’ Slow Down (ha!) and Wilson Picket’s In the Midnight Hour, which they included on their first and second Punk-scene L.P.s respectively, both released in 1977. Notably, the Jam concluded their career in 1982 with an L.P. that balanced their guitar Power Pop with a batch of bass-heavy, retro Soul originals such as Precious, Town Called Malice, and Trans Global Express along with their final single, the irrepressible Soul rave up, Beat Surrender. Meanwhile, they were still covering Soul standards—more faithfully at this point—from acts such as the Impressions, solo Curtis Mayfield, and the Chi-Lites. Postscript: The Jam’s songwriter, Paul Weller, founded a Jazzy, Blue-Eyed Soul group in 1982 with former Dexys Midnight Runners’ pianist Mick Talbot called the Style Council. I did dig them.

Aligning themselves with Black music was an intentional political move on the part of early ‘80s, white Pop bands like the Jam and Dexys Midnight Runners: Another defining feature of their movement was fierce anti-racist politics. This was a response to Thatcherism (conservative Margaret Thatcher was elected Prime Minister in 1979), a retro story itself. While it was certainly re-packaged in a softer guise, Thatcherism—like Reaganism in America—was a backlash against the progressive politics of the ‘60s and ‘70s. In Thatcher’s case, this meant in part, reclaiming the anti-immigrant politics of Enoch Powell, a former, conservative British Member of Parliament. Powell was famous for his 1968, anti-immigrant “Rivers of Blood” speech. Thatcher’s ascent looked similar to Reagan’s, who himself re-packaged George Wallace’s Civil Rights-era backlash racist populism. Dissident U.K. youth and their favorite bands, particularly the Jam’s noisier Punk circuit cohorts the Clash, were hyper cognizant of Thatcher’s reactionary politics.

While the Clash offered the most explicit lyrical attack on Thatcherism, the clearest musical response came from another subset of Britain’s retro music scene: 2 Tone Records and its roster of Ska bands. (Two-tone was shorthand for interracial). These interracial bands included the English Beat, Selector, and the Specials.

AllMusic’s write up on Ska and 2 Tone Records explains:

“Ska evolved in the early '60s, when Jamaicans tried to replicate the sound of the New Orleans R&B they heard over their radios. Instead of mimicking the sound of the R&B, the first Ska artists developed a distinctive rhythmic and melodic sensibility, which eventually turned into Reggae. In the late '70s, a number of young British bands began reviving the sound of original Ska, adding a nervous Punk edge to the skittish rhythms. Furthermore, the Ska Revivalists were among the only bands of the era to feature racially integrated lineups, which was a bold political statement for the time.”

2. Rudy A Message to You: Diaspora Pop in mid-60s London

With its bouncy nostalgic sound and its nod to mid-60s African American Pop, the ‘80s neo-Soul hit Come On Eileen is first cousins with a 1967 Ska single by British-Jamaican ex-pat musician Dandy Livingstone, Rudy A Message to You. This Ska record, released alongside his 1967 debut LP “Rock Steady with Dandy” on Ska Beat Records, is the second chronological outlier in my set.

Before the Specials revived it in the late 70s, Dandy Livingstone sang it in the mid-60s.

When it comes to what the early ‘80s revivalist kids were going for, Rudy A Message To You is a perfect find. Ska was the contemporaneous, Jamaican British version of high-energy 1960’s American Soul; both Ska and Soul were identity conscious brands of Pop, recrafting teen beats for Black youth. In a sense, 1960s American Soul and 1960s British Ska are examples of early African diaspora Pop. Shorter version: Geno Washington and Dandy Livingstone are musical soul mates.

With its off-beat Jamaican dance rhythm and catchy Kingston slang hook, Rudy A Message to You is a flawless cultural touch point. The fashionably Mod, 2 Tone band the Specials had a breakout hit with their 1979 cover of Livingstone’s original Ska record, re-titled A Message to You, Rudy. The Specials founder and keyboardist, Jerry Dammers, also founded 2 Tone Records. Though representing different particulars of the revivalist moment—Ska and Soul— the connections were clear: The Specials were early tour mates of Dexys Midnight Runners.

3. Calypso Blues: Diaspora R&B in 1950s America

A Message to You Rudy’s Caribbean off beat (or Bluebeat as it was also called in the 1960s) is clearly adjacent to another song in my set. Like the all the remaining tunes here, this one is from the 1950s: Calypso Blues, written and recorded in 1950 by pioneering Jazz and R&B piano prodigy, Nat King Cole. I included Calypso Blues—an intimate track featuring a lone bongo beat, a catchy Afro-Caribbean melody, and Cole’s casual delivery—to demonstrate the close relationship between Caribbean sounds and early, American R&B.

Working as a cool nightclub trio in the late 1930s through the 1940s, Cole, with guitarist Oscar Moore and stand up bassist Johnny Miller, set the standard for Swing, Jazz, and Blues-textured Pop; his trio’s 1946 LP “Live at the Circle Room,” recorded at Milwaukee’s Hotel LaSalle in September 1946 over nightclub chatter, clinking glasses, and occasionally, a cash register, is a master class in Blue-spiked Pop. Former New York Times Pop and Jazz music critic Ben Ratliff included the 1946 King Cole album in his book A Jazz Critic’s Guide to the 100 Most Important Recordings. King Cole’s beautiful set includes a precursor Rock & Roll version of Duke Ellington’s C Jam Blues.

Seen as a safe crossover artist by the late 1940s, Nat King Cole made a race-conscious statement in 1950 by putting his connection to the African Diaspora front and center with Calypso Blues. And the lyrics openly disparage ersatz elements of white culture:

Dese yankee girl give me big scare

Is black de root, is blonde de hair

Her eyelash false, her face is paint

And pads are where de girl she ain't!

She jitterbug when she should waltz

I even think her name is false

But calypso girl is good a lot

Is what you see, is what she got

Nat King Cole Trio, 1946, photo, Library of Congress

Calypso was a 1950s precursor to Ska. Calypso music originated in Trinidad and came to the U.K. when Caribbean immigrants started arriving in London as part of the Windrush Generation, a reference to the first ship, the MV Empire Windrush, to bring cheap labor from the U.K.’s Caribbean Commonwealth nations to London. The mass migration between 1948 and 1971 eventually fueled Enoch Powell’s anti-immigrant backlash.

Much as Southern African Americans helped spark Rock & Roll when they transported the Delta Blues to Northern American cities during The Great Migration (King Cole’s family moved from Montgomery, Alabama to Chicago in 1931 when he was 12), the Windrush Generation brought Calypso to the U.K. and helped spark the emergent London youth culture that would explode in the mid-60s Swinging London era. Collin MacInnes’ 1958 London novel Absolute Beginners depicts the early scene with literary flair. And Trinidadian-U.K. immigrant Sam Selvon’s earlier 1956 novel, The Lonely Londoners, amplifies the Caribbean perspective of the same scene.

Along with its strong dance beat and playful Pop guise, and as seen in King Cole’s Calypso Blues, Calypso featured witty, up-front socio-political lyrics. Calypso artists echoed their lyrics with their stage names, taking on “Lord” sobriquets as sarcastic commentary on their down and out Afro-Caribbean immigrant status. There was Lord Beginner and Lord Invader. And, of course, the most famous Calypsonian Aldwyn Roberts took the stage name Lord Kitchener, a spoof on an early 20th Century British military hero of the same name. (He’s the mustachioed official in WWI’s “Britain Wants You” posters, the forerunner to America’s Uncle Sam campaign.) In a great example of Calypso’s nod and wink style, Lord Kitch (Kitsch) is a wonderful play on words too, a meta one at that, deftly calling attention to the style’s own aesthetics of reclamation.

Cole’s take on Calypso gained immediate credibility with his U.K. compatriots. Trinidadian-U.K. actress-singer Mona Baptiste covered King Cole’s Calypso Blues in 1951 for the indie U.K. record label Melodisc. Melodisc, the label that also recorded Lord Kitchener and Lord Beginner, was the parent company of Blue Beat, a popular R&B and Ska label by the 1960s.

4. Junco Partner: Limbo Leanings

Featuring an off-kilter left and right hand mismatch Calypso Blues is the most rhythmically difficult song in my set. I’m still trying to get the timing of the chorus right. Calypso Blues shares its off-time beat (and the prominence of the lone percussion) with Junco Partner Blues, another Caribbean-tinged song in my set. Junco Partner Blues is much easier to swing, though; it’s got a Limbo beat.

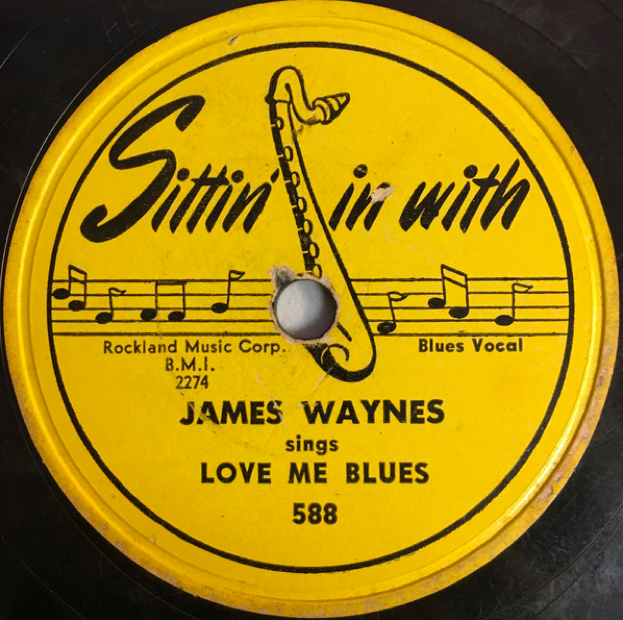

Widely considered a traditional Blues song, Junco Partner was adapted and first recorded in 1951 by a somewhat mysterious American R&B vocalist and guitarist named James Wayne (also Waynes), who was either from New Orleans or Houston, and who recorded for several independent R&B labels in the early 1950s, including Aladdin, Imperial, and Sittin’ in With.

Before releasing Junco Partner Blues on New York City-based Sittin’ in With, Wayne had a No. 2 R&B record on the label, a B-side called Tend to Your Business. Also released in 1951, it’s a spritely, sax-heavy number over a boogie-woogie bass line, and features a repetitive, crushed note piano solo that invents Rock & Roll music on the spot. Unfortunately, no one seems to knows who’s playing that rocking piano, not even Rock & Roll historian Uncle Marvy Goldberg, who I emailed to ask.

The A-Side to Waynes’ Tend to Your Business B-Side, 1951

Following a 12-bar Blues structure, Junco Partner has a much sparser arrangement than Tend to Your Business. It features see-sawing piano chords, a light sax, Wayne’s matter-of-fact vocal, and a Limbo beat tapped out on drum sticks. As the other instruments drift away, the lone drum sticks take things home solo under Wayne’s improvised vocal outro. 30 years later, the Clash directly lifted the Junco Partner drum sticks beat on their late masterpiece, Straight to Hell, from their final L.P., 1982’s “Combat Rock.”

In fact, the Clash covered Wayne’s Junco Partner itself (twice!) on their 1980 triple LP “Sandinista,” amplifying James Wayne’s precursor Ska rhythms by turning his tune into a Reggae song (Junco Partner on Side One) and a Dub experiment (Version Pardner on Side Six).

Reggae and Dub are direct descendants of Ska, and, as the centerpiece band in London’s late ‘70s music scene, the Clash were steeped in it. Originally, the Clash translated their garage rock into updated Punk songs while also echoing the Mod era’s political kinship with Caribbean immigrants. Alongside their three-chord Punk tunes, the Clash’s 1977 eponymous first LP includes a beautiful cover of Jamaican musician Junior Murvin’s reggae epic Police and Thieves and also their own original Reggae-induced Punk ballad, White Man in Hammersmith Palais, which picks up Clash front man Joe Strummer’s off-mike exhortation, “Dress back, jump back, this is a Bluebeat attack.” More and more the Clash became practitioners of Reggae and World Music, which explains 1980’s Dub heavy “Sandinista” LP. It’s worth noting that Strummer saw an early Specials show and, evidently impressed, asked the Specials to open for the Clash, giving the interracial Ska band their first prominent billing.

Junco Partner Blues is a pivotal song in my piano set. For all its Limbo leanings, it simultaneously remains a traditional 12-bar Blues number. It’s a magical record that way, protean in its ability to define two genres at once. Subtitled “Worthless Man,” Junco Partner was known as "the anthem of the dopers, the whores, the pimps, [and] the cons… a song they sang in Angola, the [Louisiana] state prison,” according to the liner notes of New Orleans R&B pianist Dr. John’s 1972 New Orleans tribute album, Gumbo, which added: “The rhythm was known as the 'jailbird beat'."

5. Shake, Rattle, and Roll: Rock & Roll structures

Tied to songwriter James Wayne’s mysterious Bluesman persona, Junco Partner inhabits the same gritty world as the defining Rock & Roll song in my set, 1954’s Shake, Rattle, and Roll by Blues shouter Big Joe Turner. (“Shake, Rattle, and Roll” was a reference to throwing dice before Turner transformed it into sexual slang.)

Originally from Kansas City, Missouri, where he worked in after-hours Jazz clubs as a cook, bartender, and eventually singer, Turner hit the national Jazz and Blues circuit in the mid 1930s and early 1940s singing his risqué Boogie-woogie Blues songs in clubs from New York City (appearing on the same bills as Benny Goodman, and later Billie Holiday) to L.A. (in a Duke Ellington revue.)

By the mid-1940s Turner was releasing rowdy R&B singles for small, independent R&B labels such as National, Aladdin, and Freedom. In 1951, R&B enthusiasts Ahmet and Nesuhi Ertegun (Turkish-American immigrants) saw Turner perform with Count Basie at the Apollo Theater in Harlem and immediately signed him to their upstart Atlantic Records label. Turner had a series of R&B hits at Atlantic, though often due only to Juke Box play; the songs were too naughty for radio.

Recorded and released in 1954, Shake Rattle and Roll was the most successful of Turner’s Atlantic releases, reaching No. 1 on the R&B charts and No. 22 on the (white) Billboard singles charts that year. Ahmet Ertegun had asked Atlantic’s in-house song writer, arranger, and producer, Jesse Stone, a former R&B band leader in both Kansas City and New York City, and the only African American on Atlantic’s staff, to write a song for Turner that would match Turner’s raucous style more than the traditional Blues tunes he was putting out. It worked.

The song includes two of the most satisfying chords to play in my piano set, the dissonant Eflat/C combo that kicks off the last four measures of every verse, and more so, the F/Eflat/A/C combo that marks the 12-bar Blues jump to the IV in the 5th measure of every chorus.

Shake Rattle and Roll’s twelve-bar Blues is the template for three other pure Rock & Roll numbers in my set: Bill Haley and His Comets’ 1954 rave up Rock Around the Clock, Elvis Presley’s 1956 Rockabilly hit Heartbreak Hotel, and Chuck Berry’s 1957 banger School Days, sometimes called, School Day (Ring! Ring! Goes the Bell).

6. Rock Around the Clock: Teenage structures

Among these three tunes, Rock Around the Clock, with a slapping standup bass in the driver’s seat, and all downhill velocity, sounds the most like Shake, Rattle, and Roll (both songs came out in 1954, the first official year of the Rock & Roll craze.) And, in fact, Bill Haley and His Comets also covered Shake, Rattle, and Roll.

I don’t have much interest in Bill Haley; he was a goofy Country and Western swing band leader—and, at 29, a bit awkward for a Rock & Roll breakout artist. Haley lucked out with Rock Around the Clock. The tune was written by a professional music biz songwriter named Max Freedman, with a writing credit also going to music publisher James Myers, who shopped it around. Myers offered the song to Haley after Haley had some success with his own 1953 Rockabilly hit, Crazy, Man, Crazy. Myers partner originally sold the song to a Virginia-based Italian American R&B novelty act, Sonny Dae and His Knights, who recorded it first, earlier in 1954, with some slight local success.

Written in 1952 or 1953, Rock Around the Clock was a take on several earlier songs, including Country icon Hank Williams’ first hit song, 1947’s Move It On Over. In turn, Williams' song was very similar to Delta Blues guitar legend Charly Patton’s 1929 Blues song Going to Move to Alabama. Born in Mississippi, Patton is widely considered one of the most important Blues musicians in history. P.s. Interestingly, despite the strong association between early Blues and African Americans, no one is really certain of Patton’ race. Historians think Patton, who had strong white and Native American features, may have had Black, white, and Native American ancestry. His song, Going to Move to Alabama, meanwhile, seems derived from early 20th Century African American Blues player Jim Jackson’s 1927 song Kansas City Blues.

Rock Around the Clock also lifts exact phrases from Jazz great Count Basie’s 1939 piano Blues frolic, Red Wagon. And Big Joe Turner himself had a record in the mid-1940s called Around the Clock Blues, a Boogie-woogie piano roll jam that sounds just like Shake Rattle and Roll, but not much like Rock Around the Clock.

Rock Around the Clock is often associated with Hollywood’s 1955 sociological teen exploitation flick Blackboard Jungle. In the movie’s final scene, teenager Gregory Miller, a thinking man’s juvenile delinquent played by a young Sidney Poitier, walks into the street under the elevated subway tracks outside his New York City high school. Crack. A hard snare drum snap kicks off Rock Around the Clock as the credits roll. The film also kicked off a jump cut in mainstream culture; Black Board Jungle is widely considered one of the key cultural shock points that popularized Rock & Roll to a broad (white) teen audience in the mid-1950s.

Rock Around the Clock has some great sad chords. I only noticed the melancholy notes because I’m not an effortless sight reader. In my hands, the famously riotous Rock Around the Clock became a mournful ballad with its gorgeous cascade of A and B flats raining down throughout the chorus. It turns out, the song sounds good fast too; I’ve finally mastered the right hand mess of sliding notes, from the D to the C and then to the A/C/Eflat chord as the chorus begins. This passage into the chorus, which settles into another sick Blues chord in the right hand, F/Aflat/C, is probably driving my neighbors crazy.

7. Heartbreak Hotel: Rock & Roll mythology

Elvis Presley’s Heartbreak Hotel is not a banger like Rock Around the Clock or Shake Rattle and Roll. It’s a sparse, minimalist 12-bar Blues. It was co-written by a Florida-based singer-songwriter, session musician named Tommy Durden and his 41-year-old friend Mae Boren Axton, an English high school teacher who wrote and successfully sold songs on the side. While it’s more a strip tease burlesque than a rocker, Heartbreak Hotel does rely on the same standby left-hand Blues scale that drives Big Joe Turner’s locomotive bass lines. Heartbreak Hotel simply uses graceful chords instead. As for the right hand, Heartbreak Hotel features the same flat fifths and slip notes that grown-up, post-War songwriters used to color Rock & Roll’s otherwise happy teen beat melodies with Existential dissonance.

Axton knew Presley’s new manager, Colonel Tom Parker, and she presented a demo of the song to Presley at the perfect time: right as Presley was making the switch from Sam Phillips’ indie Memphis-based Sun Records to the national RCA Victor label in late 1955. Presley loved the song and pressed RCA to go with it; at first, the label evidently thought it was too quirky.

Before Heartbreak Hotel and RCA, though, there was That’s All Right Mama and Sun Records. I do love the mythological anecdotes about those July 1954 Sun sessions:

Anecdote #1) The hyperactive, 19-year-old Presley breaking into a wild vamp on his acoustic guitar during an antsy breather between yet another tame and unsuccessful pass at a song from his country and R&B repertoire. In this fortuitous improvisational moment, Elvis started playing That’s All Right Mama, a number originally written and recorded in 1946 by searing Blues guitarist Arthur Big Boy Crudup. As Elvis’ electric guitarist Scotty Moore recalled in Peter Guralnick’s 2015 Sam Phillips bio: “Elvis just started singing this song, jumping around, acting the fool. Then Bill [Black] picked up his bass, and he started acting the fool, too, and I started playing with them…He [Sam Phillips] stuck his head out [of the control booth] and said, ‘what are you doing?’ And we said, ‘We don’t know.’ ‘Well, back up,’ he said, ‘try to find a place to start, and do it again.’” (pgs. 212-213, Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock’n’Roll, Peter Guralnick, 2015). They did, catching a groove for the first time in the otherwise mundane evening session. Moore concluded: “We thought it was exciting, but what was it? It was just so different, but it just really flipped Sam.” When Phillips got home late that night, he woke up his wife Becky, and as she’s quoted in Guralnick’s book: “He announced that he had just cut a record that was going to change our lives. He felt nothing would ever be the same again.”

Anecdote #2) WHBQ D.J. Dewey Phillips’ decision (Dewey was not related to Sam) to play the acetate test pressing of Presley’s suddenly vital take on That’s All Right, Mama the very next night, which lit up the phone lines during his popular, late night “Red, Hot, and Blue” R&B show. (P.s. Crudup’s original version doesn’t wail like the rest of his distorted, slow-burn 1940s Blues records—and, in fact, it clearly insinuates the up-tempo Country swing Presley dialed in to. There’s poetic justice having an African American shredder like Crudup, whose raucous guitar playing sounds like heavy metal 30 years early, at the center of Rock & Roll’s origin story.)

Meanwhile, the accompanying anecdote about speed-talking D.J. Phillips summoning Presley to the WHBQ studio for an immediate interview, and not-so subtly asking Elvis to tell listeners which high school he graduated from, is fraught American history in all its naked psychology.

Dewey Phillips, the be-bop, jive talking D.J. at WHBQ Memphis, circa 1954

Elvis’ genesis aside, I must say, RCA’s 1956 Heartbreak Hotel single (the big label ultimately went with Elvis’ instincts on the song) is one of those rare examples when the “sell out” version not only replicates the original magic, but surpasses it. The producers gave the tune a stark, small group combo treatment—stand-up bass, piano, electric and acoustic guitars, and drums—and the players shambolically followed Elvis’ vocals down his “Lonely Street” where he “cried there in the gloom.” To re-create Sun’s haunted, signature slap-back vocal delay, RCA drenched Elvis in echo. (Sam Phillips had hot-wired the original slap back effect at Sun by recording vocals live onto one tape machine's record head while also recording the playback vocal, which tracked a micro-second later, on the other head—as it piped through over a different machine!)

Presley’s decision to add Nashville pianist Floyd Cramer, famous for “bent” notes, to his original Sun band—Moore on electric guitar and Black on stand-up bass—was a master stroke. Not only is Cramer’s confident and tinkling piano solo a crowning achievement of Rock & Roll, but it puts the song in American Fake Book territory.

Heartbreak Hotel was Presley’s first gold record, hitting No. 1 on both the Billboard Pop and Billboard Country & Western charts—and No. 5 on the R&B chart, a trifecta only matched by what’s considered the world’s premiere Rockabilly single, fellow Sun artist Carl Perkins’ 1955/56 chart topper, Blue Suede Shoes. Heartbreak Hotel stayed in the Top 100 for 27 weeks and sold a million copies as the top single of 1956. The record changed Elvis Presley from a curious regional, hiccupping hillbilly phenomenon into a national sensation.

The fact that Rock & Roll was predominantly a product of Black music going all the way back to the early 20th Century —Stride, Ragtime, Boogie-woogie, Blues, Jump Blues, and R&B—has, unfortunately, turned Elvis Presley into shorthand for cultural appropriation. However, not only was Elvis’ favored position a symptom of systemic racism, a larger, brutal force that rendered Presley a mere pawn, but Presley himself was, relatively speaking, a progressive Southern white teenager when it came to race. He was basically an R&B fan boy, a Southern town odd ball at the white High School who wore his greased hair long and aspired to Black styles.

The woke factor was even more pronounced for adults Sam Phillips and Dewey Phillips. Sam Phillips, who made Memphis-based Blues guitarist B.B. King’s earliest recordings in 1949, went on to found Sun Studios in 1952 with an initial focus on recording Black musicians, including Howlin’ Wolf, Bobby “Blue” Bland, The Prisonaires (inmates at the Tennessee State Penitentiary), Roscoe Gordon, Junior Parker, and Ike Turner and His Rhythm Kings. Turner and the Rhythm Kings have been credited with recording the “First Rock & Roll record,” Rocket ’88, at Phillips’ nascent studio in 1951. Ike Turner was on staff at Sun as a talent scout and producer. Meanwhile, D.J. Dewey Philips’ “Red, Hot, & Blue” radio show featured a boldly integrated playlist, amplified by his hillbilly/beatnik patter. Given the context of the times, the nascent Civil Rights era, none of this was cringe-worthy virtue signaling nor embarrassing liberal paternalism out to romanticize or, by default, other Blacks. These were earnest gestures to give wider exposure to the African American artists they dug

Unfortunately, despite Elvis’ own gregarious, public deference to the Black artists he imitated— “Let’s face it,” he said of his rhythm and blues influences during a 1957 interview, “nobody can sing that kind of music like colored people. I can’t sing it like Fats Domino can. I know that”—Black Artists didn’t get the credit or compensation they deserved during this era.

8. Chuck Berry

Electric guitar innovator and prolific songwriter Chuck Berry was one African American artist who fought for his due. And got it. His music estate at his death was estimated to be worth around $20 million.

Angry about his initial Chess Records contract (Berry was startled to see that Cleveland Rock & Roll D.J. Alan Freed, a business pal of the Chess brothers, got a writing credit on his debut single Maybellene), the savvy guitarist quickly got up to speed on contracts. He subsequently locked in royalties and other terms that assured fair payment—sometimes including up-front cash for gigs and films. Barry, who also fought legal persecution with counter-legal claims asserting racism, scoffed at the bigotry that tried to relegate him to the background.

Berry was raised in a middle class St. Louis family in the 1930s and 1940s; his dad was a contractor and his mom was a public school principal. Berry took up music in his teens, playing Blues guitar, but also getting into trouble and landing in reformatory for armed robbery. He continued developing his musical talents in reformatory, and went straight upon his 1947 release: getting married, working in local auto plants, working as a janitor in the apartment building where he lived with his wife, and getting a beautician license.

He also continued pursuing music in and around St. Louis with Blues pianist and collaborator Johnny Johnston. Berry started developing a sound that mixed the styles of two African American electric guitar greats: the guitar bends, syncopated triplets, and showmanship of mid-1940s Blues guitarist T. Bone Walker and the Jazz riffs of Carl Hogan, the lead guitarist in Louis Jordan’s famous Jump Blues combo, the Tympany Five. (Listen to Hogan’s guitar intro to Jordan’s 1946 hit Aint that Just Like a Woman? If you aren’t aware of Berry’s heist, your jaw will drop.) Berry also added the calm and precise vocal style of Nat King Cole (as opposed to Blues shouters like Wynonie Harris and Big Joe Tuner). Berry recorded a few tracks in 1954, but it wasn’t until a year later when he met Chicago’s Chess Records success story Muddy Waters, another one of Berry’s guitar heroes, that Chuck Berry blew up the world.

Mississippi-to-Chicago transplant and Blues great Muddy Waters (real name McKinley Morganfield) connected Berry with Chess Records owner Leonard Chess in May, 1955. Ironically, Berry, in a style that seemed like Muddy Waters on speed, displaced the Chess Blues star by releasing an unmatched string of perfect Rock & Roll singles on the label between 1955 and 1959. They are worth listing. I’m leaving several out, but these are my favorites, in chronological order:

Maybellene (the height of backbeat rock, with its bent out of shape, hall-of-fame and distorted guitar solo);

Roll Over Beethoven (an off-hand, gorgeous mess);

Too Much Monkey Business (hi, Bob Dylan);

You Can’t Catch Me;

School Days;

Sweet Little Sixteen;

Reelin’ and Rockin’ (that crazy piano!);

Johnny B. Goode (see Carl Hogan);

Around and Around (a minimalist tour de force which paralleled contemporaneous, early, avant-garde computer music with its emphasis on looping, overlaid counterpoint, and mounting repetition, which Berry does without tape splices or overdubs, but rather through crafty implication);

Carol;

Sweet Little Rock and Roller;

Little Queenie;

Bye Bye Johnny;

and Wee Wee Hours (Maybellene’s flip side, a gone Blues rave up).

My sense is that most people aren’t familiar with Wee Wee Hours. The musical conversation between Berry and his unconventional pianist Johnston makes for delightful eaves dropping. On the B-Side of what may be the first intentional Rock & Roll record, Berry’s debut single Maybellene, Wee Wee Hours’ lyrics seem to ridicule the elderly Blues, even as Johnston is lighting it up on unhinged Blues piano in the background:

“One little song

For a fading memory

One little song

For a fading memory.”

In his groundbreaking academic study of early Rock & Roll, The Sound of the City, music historian Charlie Gillett highlighted Johnston’s piano playing as the secret ingredient to Chuck Berry’s records, a seemingly contrarian observation when it comes to a catalogue known for its game-changing electric guitar acrobatics. It’s a canny observation that’s always stuck with me—and rings true when you listen closely to Berry’s records for the catawampus piano mixed in the background. It also made me fall in love with quirky Rock & Roll piano playing. Gillet writes: “…the effect was complicated by a piano that seemed to be played almost regardless of the melody taken by the singer and the rest of the musicians…few rock ‘n’ roll performers dared to challenge the conventions of harmony in this way, and part of the immediately recognizable sound of Berry’s records was the interesting piano playing.” (pg. 81, The Sound of the City, Charlie Gillett, 1970)

I don’t know why I chose School Days for my piano set. Roll Over Beethoven, Around and Around, Reelin’ and Rockin’, Maybellene, and Wee Wee Hours are my favorite Berry songs. But what I’ve learned by spending time with School Days is this: The right hand melody line, set over the standard 12-bar blues chord progression in the left hand, is absolutely un-intuitive—the notes don’t land when and where your brain thinks they should. For example, what’s with going from the E flat in the 9th bar to the disorienting Gflat? (The song is in the key of Eflat major, which does not include Gflat). But once you get it down, School Days is addicting to play, even as it remains cryptic.

9. Get a Job: Rock & Roll as Doo-wop

Just as Junco Partner gave me the perfect segue from Caribbean mode to Rock & Roll mode, the Philadelphia-based Silhouettes’ 1957-58 mega-hit Get a Job—No. 1 on both the Pop and R&B charts in 1958—provides the perfect segue from the pure Rock & Roll of School Days, Heartbreak Hotel, Rock Around the Clock, and Shake Rattle and Roll to Rock & Roll’s glorious sub-genre, Doo-wop. (To be clear: I’m not saying Get a Job literally provides the segue from Rock & Roll to Doo-wop; if anything, it nudged Doo-wop, which emerged several years before 1957’s Get a Job, back toward Rock & Roll. I’m just saying for purposes of my set, Get a Job provides the bridge between the two genres.)

Technically, Get a Job is more Rock & Roll than Doo-wop: It features a honking Blues-happy sax solo, a propulsive piano, an exaggerated backbeat in the chorus—banged out on a rocking floor drum, and a signature V-back-to-the-IV 12-bar Blues turnaround in the penultimate measure of the signature melody line. It’s the song’s novelty vocal play, particularly by bass vocalist Raymond Edwards—"Dip dip dip dip dip dip dip dip/ Sha na-na nah/Sha na-na-na-nah nah”—that make Get a Job a Doo-wop classic. Vocals were central to Doo-wop.

Get a Job’s swinging “Sha na-na nahs” make the same historic move Chuck Berry made. Just as Berry sped up the Blues to make it youth music, or more accurately, spiked the Blues to make it Pop music, Doo-wop transformed another elderly African American musical style: Vocal Harmony music, which was the secular version of Gospel. In Doo-wop’s case, it took the opposite approach than Berry: Doo-wop spiked Vocal Harmony music with doses of old-fashioned Blues and R&B.

Vocal Harmony music was dominated by overly sentimental ballads; the indulgent Ink Spots, with their dramatic spoken-word breakdowns, are the most famous vocal harmony group. Despite the new R&B touch, the dreamy mood of Vocal Harmony persisted in Doo-wop. Doo-wop simply re-invented the staid 1940s Ink Spots’ church-adjacent sound with an energized teenage groove. Get a Job may be the most energized song of the Rock & Roll era—it just goes, daddy-o!

Historic Footnote: Unlike the Ink Spots and other secular Vocal Harmony groups, the Gospel vocal groups themselves, such as the Golden Gate Quartet and the Soul Stirrers had already been dosing Gospel with a little bit of R&B as early as the 1930s when they first emerged on the scene. The roots of both Rock & Roll and Doo-wop, and Soul too, are present in Gospel. (As a teenage phenomenon, Soul music progenitor and heart throb Sam Cooke got his start in the 1950s iteration of the Soul Stirrers.)

Doo-wop’s defining feature is the well-known, melodramatic “1950’s Chord Progression.” A slight tweak of the 12-bar Blues I IV V sequence, Doo-wop’s signature move is: I vi IV V. This progression establishes a yearning sensation by immediately creating a more circuitous route to the dominant V, setting up a homesick musical journey by initially overshooting the V, and then teasing its way back.

With this aching cadence turning aspiring teen vocalists into composers on city street corners nationwide, Doo-wop singles and their woeful tales of young love started coming out in droves in 1953, most notably the B-Side Gee sung by Harlem-based Daniel “Sonny” Norton and his vocal group the Crows. Formed in 1951 by five aspiring NYC teen vocalists, the Crows were Apollo Theater’s Wednesday amateur night favorites, where they were discovered in 1952 by music agent Cliff Martinez. Martinez eventually steered the Crows, now with an electric guitarist added to their pure vocal group set up, to George Goldner’s local indie label, Rama Records. Goldner booked Norton and the Crows for a session as the backup group to African American R&B trailblazer, pianist and singer Viola Watkins. Gee, with its background “Do da-da doot do-dos,” was written by the group’s baritone William Davis, and arranged by Watkins. They recorded it as an extra song in the April 1953 Watkins’ session and released it as an afterthought that May. It took a year, but by the spring of 1954, Gee went to No. 2 on the R&B charts, No. 14 on the Pop charts, and ultimately sold over a million records by the end of 1954—the first Doo-wop song to hit that milestone, bringing Doo-wop to the mainstream. Accordingly, Gee is often mentioned in the endless debate over what constitutes the first Rock & Roll record. (Gee is an up-tempo number as opposed to the Crows’ dreamier Rama Doo-wop records: Gee’s A-Side I Love You So, along with June 1953’s Heartbreaker and 1954’s attempts to ride Gee’s coattails, Miss You and Untrue. The 1954 sessions also included two up-tempo Gee knockoffs, Baby and I Really, Really Love You. None of these records were hits, though in my opinion, the Crows’ ballads are elementary Doo-wop perfection.)

Doo-wop was the bright core of a broader, nascent counterculture that would ultimately shake up America for two decades with a Civil Rights, Rock music, youth, and DIY aesthetic. Doo-wop has a notably innocent sound for something that would bloom into revolution. This contradiction makes for satisfying detective work. Doo-wop lyrics can come with witty sendups of capitalism, sly digs at racism, and narratives about police brutality. (Doo-wop’s trans-Atlantic co-conspirator, early ‘50s London-based Calypso, was more up front about the political agenda at hand, which, in the case of Calypso, also included challenging sexism. Sadly, Doo-wop didn’t get the memo on that fight.)

You’ll mostly find the politics of doo-wop reflected symbolically in the split personality of the music itself: The songs feature grandiose melodies cast in spare minimalism; they feature gleeful energy backed by sad chords. These basic contradictions mirror the central dissonance that haunted the lives of 1950s African American youth. Doo-wop’s hopeful American idealism comes with a gloomy footnote: the American Dream is great and all, but we don’t have access! Academic and Blues historian Albert Murray makes the very same observation about the Blues in his classic book Stomping the Blues, writing: “Even the most exuberant stomp rendition is likely to contain some trace of sadness as a sobering reminder that life is at bottom, for all the very best of good times, a never-ending struggle.” [pg. 17, Stomping the Blues, Albert Murray, 1976]

In his ur text, 1970’s The Sound of the City, Rock & Roll historian Charlie Gillett has a similar thing to say—specifically about the Silhouettes’ Get a Job. Gillett wrote, “The Silhouettes were revolutionaries in disguise to judge by the scarcely intelligible lyric of their top ten hit Get a Job (1958): the lyric could easily have been fitted into the opening chapter of Richard Wright’s novel Native Son.” [pg. 75, The Sound of the City, Charlie Gillett, 1970.]

Get a Job certainly addresses the elusive “American Dream,” capturing the economic plight of African Americans.

Tell me that I'm lying

'Bout a job that I never could find

Sha na na na, sha na na na na

Sha na na na, sha na na na na

Sha na na na, sha na na na na

Sha na na na, sha na na na na

Dip dip dip dip dip dip dip dip

Mum mum mum mum mum mum

Get a job, sha na na na, sha na na na

The Silhouettes, 1957

10. Earth Angel: Doo-wop mythology

The two other Doo-wop tunes in my set, The Penguins’ 1954 hit Earth Angel and the Five Satins’ 1957 record In the Still of the Nite (the shorthand slang spelling was meant to distinguish the teenage tune from Cole Porter’s unrelated, 1937 American standard) track more to the I vi IV V “50’s Progression” than Get A Job’s R&B Doo-wop hybrid.

P.s. David Bowie and the early 1970s ‘50s rock revivalists, who dressed up their nostalgia in camp, glitter, and distorted electric guitars, relied heavily on the Doo-wop progression. Divine examples include: Bowie’s Five Years, Lady Stardust, and Drive in Saturday; T. Rex’s Monolith and Girl; the New York Dolls’ Lonely Planet Boy; several cuts on 1975’s “Rocky Horror Picture Show;” Elton John’s Crocodile Rock; and Glam-to-Punk pioneers Suicide’s Cheree. All these tunes are essentially Doo-wop songs. P.p.s. Precursor Punk music like 1972 Bowie, with its 1950s revivalism, quickly gave way to the 1960s retro fetishisms of ‘80s bands like the Jam, the Specials and Dexys Midnight Runners that I noted earlier. Basically, 1970s proto-Punks and 1980s Punks and New Wavers, reveled in Rock & Roll’s first decade, the mid-50s to the mid-60s. You’ll notice that by the 1990s, the Grunge craze moved on to fetishizing the next decade’s jam, 1970s hard rock.

Mid-1950’s Doo-wop breakthrough Earth Angel may be the prettiest song in my set. Every section features a gorgeous flatted note, adding a melancholy flight of fancy to the sweet melody. I love playing Earth Angel late on Saturday nights when I come home a little sad after drinks on the drag. In addition to the sneaky Blue notes in every measure, my favorite thing about the Earth Angel arrangement is the transition from the single note right hand melody to a chorded version during the last two verses.

The story behind Earth Angel is as epic as the mythology of Elvis’ Sun sessions.

The early 1950s L.A. youth music scene revolved around local indie R&B label Specialty Records and their star singer, 21-year-old Doo-wop sage Jesse Belvin, a Jefferson High School graduate; Jefferson High School was a mecca of (African American) music education that produced a parade of legendary Jazz and R&B musicians. In 1953, four local teens (2 who had just graduated from Jefferson’s rival Fremont, and two current Fremont students) formed the Penguins, named after the Kool cigarettes mascot. One member of the vocal group, 19-year-old Curtis Williams, brought Earth Angel, which he’d been writing with Belvin, to the Penguins. (The song echoed Belvin’s own 1952 Specialty single, Dream Girl). The Penguins recorded it for L.A-based indie R&B, Gospel label Dootone in the fall of 1954. As opposed to Art Rupe’s Specialty, which admittedly had an amazing African American roster—the Blind Boys of Alabama, Little Richard, Lloyd Price, Percy Mayfield, Roy Milton, and Sam Cooke’s Soul Stirrers— Dootone was Black-owned. Dootone was founded in 1949 by 1940s African American band leader Walter “Dootsie” Williams; for the first two years of Dootone’s existence, the label was called Blue Records. The Penguins recorded the song in the garage of Williams’ relative Ted Brinson, a Big Band era bassist; Brinson played bass on Earth Angel. The young Curtis Williams played piano.

Much like the Dewey Phillips story—only this time with a nearly all African American cast—Williams brought the acetate demo recording, with its accidentally lopped off opening measure (a quirk of music history) to local taste maker, African American record shop owner John Dolphin. Dolphin’s Central Ave. shop, Dolphin’s of Hollywood, founded in 1948 and open 24 hours-a-day, was a West Coast Jazz and R&B mecca that doubled as a broadcast studio for KRKD, where L.A. D.J. Dick Hugg, a white R&B enthusiast, often manned the booth. Hugg played the sparse dub mix and the excited radio audience response was immediate. Williams passed on the planned overdubs, and Dootone pressed the song as is. By early 1955, Earth Angel went to No. 1 on the national R&B charts, and it cracked the Top 10 on the Pop charts (#8)— a few notches better than the Crows’ earlier crossover hit, Gee.

Interesting footnote: Gee also got its boost from John Dolphin’s record shop broadcast.

Doo-wop historian Marv Goldberg writes about Gee’s 1953 release:

“Its initial reception was nothing to write home about. ‘Gee’ may have had potential, but it was sure taking its sweet time. While the record itself was a Pick Of The Week in the trades on September 19, it was [the A-Side] ‘I Love You So’ that was reportedly making noise in Dallas, St. Louis, Nashville, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles. ‘Gee’ finally became a Tip in Detroit on November 28, six months after its release. Then, in December, it started riding the local charts (becoming a Tip in Los Angeles on December 19).

“It looks like ‘Huggy Boy’ was the cause. Dick Hugg was one of the DJs who broadcast from the front window of John Dolphin's record store in Los Angeles. He had played ‘Gee’ months before, and decided he didn't like it much. The disc ended up with his girlfriend, who really loved it. One night they got into a fight and, to make up, Huggy Boy played the song over and over on the air for her. For some reason, that episode triggered an explosion of sales in LA. Kids who were lukewarm to the song when they heard it once in a while, went nuts for it when it was played non-stop.” (Marv Goldberg’s R&B Notebooks, The Crows, 2004.)

11. In the Still of the Nite: Doo-wop mythology, Pt. 2

1956’s Pop hymn, In the Still of the Nite, glowing with “50’s Chord Progression” left hand arpeggios (F/D/Bflat/C in this case), rivals Earth Angel for heavenly Doo-wop beauty.

There’s not much of an origin story to the song, though. Recorded for a small New Haven, Connecticut label late in the Doo-wop craze by local African American quintet the Five Satins, and written by group member Fred Parris, the record was a minor hit, but hardly a smash like Earth Angel or Get a Job. In the Still of the Nite went to No. 24 on the Pop charts and No. 3 on the R&B charts.

Its ascendance (and transcendence) seems to have happened after the fact, coming out on influential compilations (as early as 1959) and on subsequent movie sound tracks (Dirty Dancing in 1987, for example.)

I’m not sure when the song grabbed me—maybe in high school when I realized David Bowie was keen on the I vi IV V “50’s Chord Progression.” In fact, as a 15-year-old Bowie rip-off artist, I wrote a song called Punk Love that appeared on my 1983 LP “Josh Feit Right Now” and revolved around a series of snide “doowop doowop/shoowop shoowops,” mimicking the Five Satins background vocals with a Johnny Rotten POV. My high school songwriting pal D. Shiller played the famous ‘50s teen cadence on distorted electric guitar, which I backed up on a chiming acoustic, eventually giving Shiller the runway to start a barbed wire solo.

In college I thought In the Still of the Nite was a holy text, associating it with my cool Jazz D.J. roommate, a talented musician and crooning vocalist named Rich Kurschner from New York City.

I felt vindicated when I later learned that famous rock critic Robert Christgau worshiped In the Still of the Nite.

When I set out to have a Rock & Roll set, In the Still of the Nite was the first song I chose to learn.

12. At the Hop: A Pop sensibility

Another Rock & Roll-Doo-wop hybrid in my set is late 1957’s No. 1 hit At the Hop by Danny and the Juniors. Like the Silhouettes, whose Get a Job also combined Rock & Roll and Doo-wop, Danny and the Juniors were from Philadelphia. Unlike the Silhouettes, though, Danny and the Juniors were white white white.

Danny and the Juniors (with 16-year-old Danny Rapp on lead vocals) were a high school Doo-wop act originally called the Juvenaires. They came to the attention of a local record producer named Joe Madara who helped them write and record a demo, Do the Bop. After one label rejected it, they got the recording into the hands of “American Bandstand” TV host and Philadelphia D.J. Dick Clark. Clark liked it, but suggested they change the archaic title. (He also suggested they change their name.) After they revamped the song, Clark asked the group to perform on “American Bandstand,” which quickly catapulted At the Hop to No. 1 on both the Pop and R&B charts. I first heard the song as a little boy when my Brother took me to the 1973 nostalgia film American Graffiti. I was captivated and have loved it ever since.

Indeed, I’m not trying to be dismissive of Danny and the Juniors by calling them white; I dig this record. Its driving piano intro (openly copped from Sun Record’s bona-fide Rock & Roll keyboard master Jerry Lee Lewis), its majestic Doo-wop vocal intro (and subsequent low Doo-wop swoops— “Oh, baby”), its infectious internal rhymes (“All the cats and the chicks can get their kicks at the hop”), and the Blues-y Bflat over the low G and then repeated over the lower C in the chorus, make for a dynamic and dynamite record.

I point out their race because despite the song’s Doo-wop and 12-bar Blues trappings, it does a curious thing: Rather than going to the traditional flatted VII for a pure Rhythm & Blues sound during the verses, it descends from the VI back to the V instead—and then continues as if nothing had changed: VI V III. By removing the flatted VII from the traditional Blues bass figure, they shift the mood from hurt-so-good Blues to actual feel-good Pop. It also frees the right hand to go with a sunny melody rather than a stormy one. To my ear, this moves At the Hop away from its African American Rhythm & Blues influences and toward white American glee club music.

This is not to say white musicians weren’t playing and recording fiery Rock & Roll. Jerry Lee Lewis, as I just said, was a demon at the piano. And I put Elvis Presley’s Heartbreak Hotel and Bill Haley and His Comets’ Rock Around the Clock in my set because I think they’re exceptional Rock & Roll songs. And by the way, earlier, I failed to call out Danny Cedrone’s wild Rock Around the Clock electric guitar solo. His innovative, white lightning fusion of Jazz, Blues, and Country during the historic Bill Haley recording session rivals Chuck Berry’s guitar craftmanship. Incidentally, like Berry, Cedrone’s tricks sound a lot like Louis Jordan’s Jazz/Jump-Blues guitarist Carl Hogan.

Ultimately, though, At the Hop’s Pop sensibility takes us full circle back to those 1980s New Wave bands like Dexys Midnight Runners and their Pop interpretations of 1960s Soul. Come On Eileen is as much a call out to ‘50s sock hops as it was to groovin’ ‘60s Soul. Specifically, it’s a shout out to At the Hop: Kevin Rowland’s “Too ra loo ra too ra loo rye aye” C to C octave vocal climb is a direct homage to Danny & the Juniors “Ba ba ba ba” D to D octave vocal jump that starts At the Hop.

In turn, Danny and the Juniors did some call outs of their own. First, in general, the tune is an immaculate homage to all the the musical styles that inform my Rock & Roll piano set. The Wikipedia entry for At the Hop sums that up well: “Musically, it [At the Hop] is notable for combining several of the most popular formulas in 1950s rock'n'roll, the twelve-bar blues, boogie-woogie piano, and the 50s progression.”

But there’s also a literal shout out in At the Hop’s lyrics. 16-year-old Danny Rapp sings:

“When the record starts spinnin'You Chalypso when you chicken at the hop.”

The Chalypso was a late ‘50s dance craze inspired by Calypso. And with that, At the Hop cues Nat King Cole’ Calypso Blues > Dandy Livingstone > James Wayne > Big Joe Turner > Bill Haley and His Comets > Elvis Presley> Chuck Berry > The Silhouettes > The Penguins > The Five Satins > and those 1980s outliers, Dexys Midnight Runners.

©Absolute Besmirchers, August, 2021